hi. It’s been a while. I’ve been hesitating to write this newsletter, mostly because writing this down is another step in the assimilation of my grief.

Within exactly two weeks of another, my family lost our beloved dog Sherman Chasqui Silva and the patriarca of my family, my Abuelito Braulio Pilares Rosas. The time in between April 23rd and May 7th was one in which I felt that my family’s heart was compressed, flattened, and placed into a food processor.

While these losses were like Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “Cronica de una muerte anunciada,” I’ve learned that losses are not softened even if they’ve been stewing in the anticipatory grief category.

As a result of these consecutive losses, I ended up Flatbush’s Urgent Care, for dehydration. Maybe it was the quick international travel or maybe it was the amount of tears I shed in that timeframe (enough to make a sweater really, a-la-Spongebob). After resting and drinking copious amounts of electrolytes, I was back to “normalcy” within the next couple of days. Truthfully, I had pushed myself too much. My workplace has a 3 day bereavement policy, and so I was immediately working post-landing.

Some words about Sherman.

Sherman Chasqui Silva

Sherman was an 88 pound yellow Labrador retriever that loved pan and his family. Sherman regularly ate Publix Chicago rolls and in his past life was either a baker or went to prison for stealing bread a-la-Jean-Valjean.

Sherman was a product of divorce, his original humans ended up abandoning him. My papa found Sherman in The Flyer. The first thing that Sherman did when he met me was stand up on his two paws and lick my face. He came home with us immediately.

Sherman, as a true Floridian, enjoyed sunbathing directly under the air-conditioning vent. I used to spoon Sherman and alternatively marvel at his webbed paws that carried a comforting Fritos smell.

Sherman, while not a trained emotional support animal, sat next to me in the summer of 2017, when I struggled through panic attacks for the first time. Sherman was also my confidante and friend during the pandemic.

I was at home alone with my parents and Sherman in Florida for the majority of the pandemic. Sherman marked my days, creating a steady rhythm by pushing the door open and licking my face to start my mornings. Sherman probably had thoughts about my repeated listening of Mitski during this time period, but withheld outwards signs of judgement.

At the end, Sherman was euthanized after valiantly fighting cancer for nearly a year, far outliving his original prognosis of two to three months. To cope during his illness, my brother and I sent each other news of every celebrity Sherman outlived. The Queen? Gone. Alan Arkin? Gone too. Sherman? ALIVE!

On Sherman’s last day, my papa and I took him on the longest walk of his life. I’m not sure whether it was the candle I lit to San Martin de Porres that allowed Sherman to have a last couple of beautiful days, but either way I am grateful I was there. I fed Sherman a whole bag of Chicago rolls and two ice cream cups. I looked him in his eyes and told him that I loved him. I thanked him for saving my life.

Sherman died at home, laying on top of the two orthopedic beds I had previously bought him. A quick aside, I prioritized Sherman’s sleep quality over mine, I slept on a half-sunken mattress that was missing a leg for over year, lol. Sherman’s last minutes were spent being hugged by my papa, as my brother and I patted his chest.

I told Sherman it was okay to let go when he was ready.

In retrospect, I realize I was speaking to myself more than Sherman. Most days I tell my boyfriend that I’m doing better.

Last Thursday, my boyfriend and I took our first Ikea trip together, which I had anticipatorily romanticized by repeated viewings of 500 Days of Summer. In the Kids’ section, I found a large yellow retriever plushie and I lost my shit… grief is a humbling experience.

After Sherman transitioned into his own sky-panaderia, I flew back to New York. When I took the Q train to work the next day, a man was wearing a embroidered jacket, that read “You’re Gonna Carry That Weight.”

Which is exactly what happened. My Abuelito Braulio had been succumbing to Alzeimher’s. It was a process that had taken a decade and that involved the slow and painful erasure of who he was. I had been grieving my Abuelito for a long time, but I was having fitful dreams that coupled with his health updates, let me know his transition was imminent.

Anticipatory grief was filtering into my dreams. I had a dream where I was wearing a bridal gown and veil, staring at my reflection in the mirror. When I spoke to my mama, we both agreed; a death omen. It’s common knowledge that seeing oneself as a novia is a death omen, there’s room for feminist commentary on equating death to marriage, but that’s another substack newsletter.

Two nights before my Abuelito passed, another dream, this time with no need for interpretation.

I was in El Angel Cemetery, in Lima, which also double’s as Lima’s largest quiet space, dotted between mourners, Donofrio ice cream carts and grave cleaners with Super Mario-impossibly high ladders. El Angel houses Jose Maria Arguedas and Chabuca Granda, but most importantly to me, my paternal Abuelos, Francisco Silva y Margarita Roncal.

In my dream, my mama and I were pushing my Abuelito in his wheelchair there. Mama was livid, a thief had stolen the headstone marker of Abuelita’s grave. We were buying a replacement headstone and paying thousands of soles. Mama was urging me to hurry up because we were going to miss our flight back to the U.S.

Even in my dream, I was worried, how could we leave Abuelito? We couldn’t take him with us, because of his disease, he’d have no idea where he was. My mama was pressuring me to go, but I was trying to figure out who would take Abuelito back to his home. I felt desperation, of the prospect of being separated from him.

I woke up suddenly. Lost for a second as to which America I was in.

Two nights later, I lit my San Martin de Porres candle for the second time. Abuelito had been admitted to the hospital for pneumonia. Even if he’d leave the hospital, his life quality would be non-existent. I prayed to San Martin, and asked him to intercede to end his suffering.

The next morning on May 7th, I woke up to 10 missed calls, from my brother and my papa. I already knew he was gone.

In Peru, the space between death and burial isthisclose. My Abuelito was to be buried the next day at 4pm. Within the span of 4 hours, I bought a flight to Peru, asked for bereavement leave from work, and did the worst packing job of my life. I also ran to the bank with my boyfriend to get a cashier’s check to put down a security deposit for our new apartment, since we were moving in 11 days.

All my funeral clothes were too slutty.

All my black clothes was either skintight, had a mini-hem, a bosom peephole or was covered in lace or fringe.

I laughed at my wardrobe. Very irresponsible of me to not have mourning clothes ready, but also kind of funny? I chose what I thought were the two most respectable outfits among them.

It wasn’t until I sat down in the airplane on the way to Lima that I allowed myself to really cry. I was officially desabuelada. Not a single grandparent left. I felt like a plant whose roots had been chopped off. Who am I without my elders?

Mi Abuelito Braulio y mi Abuelita Rita.

My Abuelito Braulio taught me about Ayni, huaynos, and how to approach life with unfiltered joy. During my flight, I kept getting memory flashes of our time together and had stinging eyes by the time I landed to Lima’s Aeropuerto Jorge Chavez.

I arrived, showered, and changed into my first mourning outfit, a mesh and fringe covered 80’s shoulder padded dress. My Abuelito’s wake had started a few hours beforehand.

His wake was held at his home, in Canto Grande. My Abuelito had done so much for his community, cofounding a school, a park, and a cemetery. He had even influenced the naming of his community to be Machu Picchu.

He was known for being generous, almost to a fault, giving away whatever he had to those left fortunate. In fact, my Abuelita, once accused him of infidelity because he gave away his mattress when a woman with a baby knocked on his door. She was begging for food and money, and he gave her what he had. My Abuelito was telling the truth, he had never seen this woman or baby before, his generosity over his lifetime, never ceased to baffle my Abuelita. He loved futbol, having played in his youth as a goalie, and later became the regional director for the youth soccer league in Lima. My Abuelito would handwash countless futbol uniforms, much to my Abuelita’s chagrin. There’s more to write about my Abuelitos, but I'm doing a hail Mary and hope there’s amply time in my lifetime to continue writing.

I arrived to his wake around 11pm that night. Neighbors, family and friends were gathered inside his home and on the street. There were at least 7 funeral wreaths that had been gifted in his memory.

Abuelito was in his sala. His coffin was flanked by wreaths, in the same place where the dining room table was, where he used to help my Abuelita prepare me humitas. I hugged my mama, and we cried together.

There was a cross hanging over his coffin. I thought about how my Abuelito was not remotely religious, and only went to church when bribed by my Abuelita for 20 soles.

That night, amidst the “mas sentido pésames,” and hugs, I played one of my Abuelito’s favorite huaynos, Yauliallay by the Campesinos.

“El amor es una planta yaulillay

Que crece y se marchita yaulillay

Que crece y se marchita yaulillay

Bajo la sombra de un mal pago yaulillay.”

I remembered how we danced huaynos together the night of my Quinceañera. I thought that maybe we would have appreciated that his music was playing on the last night he would spend home.

The next day, I wore my second mourning outfit, for the continuation of his wake and burial. It was a lacey halter jumpsuit, that was promptly censored by my parents as soon as they saw it. My mama pushed her pussybow blouse into my hands. On it went.

When we arrived to his wake, I was struck by how many people were still coming to pay their respects. His friends, arrived with canes or pushed in a wheelchair by their children.

My brother and I ordered chicharron con camote sandwiches, because as he said, it may be a wake but people are still hungry.

That morning, I introduced myself countless times as “soy la nieta de Don Braulio.” Nothing could have made me prouder.

I want to acknowledge how lucky I am to have been able to make his wake and funeral. Many in the disapora miss these events, due to money, resources and the ability to travel. Most of the time, we don’t get to say goodbye. I had been unable to attend my Abuelita’s funeral in 2014, and I still carry that sorrow in my heart.

We did a short procession to the park my Abuelito founded, Parque Ayni. He spent his days transforming this previous dumping ground into a picturesque garden. He built it so my Abuelita would have a place to sit and be among flowers.

As his nieta, I was responsible for leading the way with my other prima, Michelle. We held flower arrangements in our hands, while our tios and primos carried Abuelito’s casket. The rest followed in the procession, throwing flower petals from the wreaths, a final confetti to honor him.

When they reached Parque Ayni, they lowered Abuelito three times in as a despedida, while we shouted his name.

“Braulio Pilares!

PRESENTE!

Braulio Pilares!

PRESENTE!

Braulio Pilares!

PRESENTE!”

I stayed with Abuelito until the door was shut on the hearse. We began the chaotic drive to Campo Fe, the cemetery. Did you know that traffic in Lima will yield to no one? Not even the dead?

Right before Abuelito was lowered into his grave, we made a line to say our final goodbyes. I bowed, touching my knee to the ground and pressed my palm against his coffin.

Right before the Campo Fe Diggers started, a bird landed on top of the soil that was to cover Abuelito’s grave. I stared at it, and it flew towards me before disappearing.

I know it sounds hokey to say that the bird was him, or some form of representation of transitioning on. I’ve come to believe that while I might have scoffed at this as terrible use of CGI in a film to create closure, that what I felt and saw was real.

A few days later, on Día de la Madre, my tia gave us Abuelito’s photo albums. I had grown up hearing him narrate his memories when he showed me his albums.

It turns out that Abuelito had more photo albums than he had let on. As we flipped the pages, it dawned on us that he been quietly swiping photos from each family member’s album and homes.

He had squirreled away the best photos of our family, creating a precious, chaotic album, in which weddings lived next to infancy photos that were 50 years apart or more. His album stopped circa 2011, which I tracked from photos of his only great-grandchild, my sobrino. I realized that his photos stopped when his diagnosis started.

I had never seen most of these photos, which included some from my childhood. My tias saw wedding photos they had forgotten about.

It was for me, a profound affirmation. I understand that the care and love we had for him was being refracted back into my hands while grasping his albums.

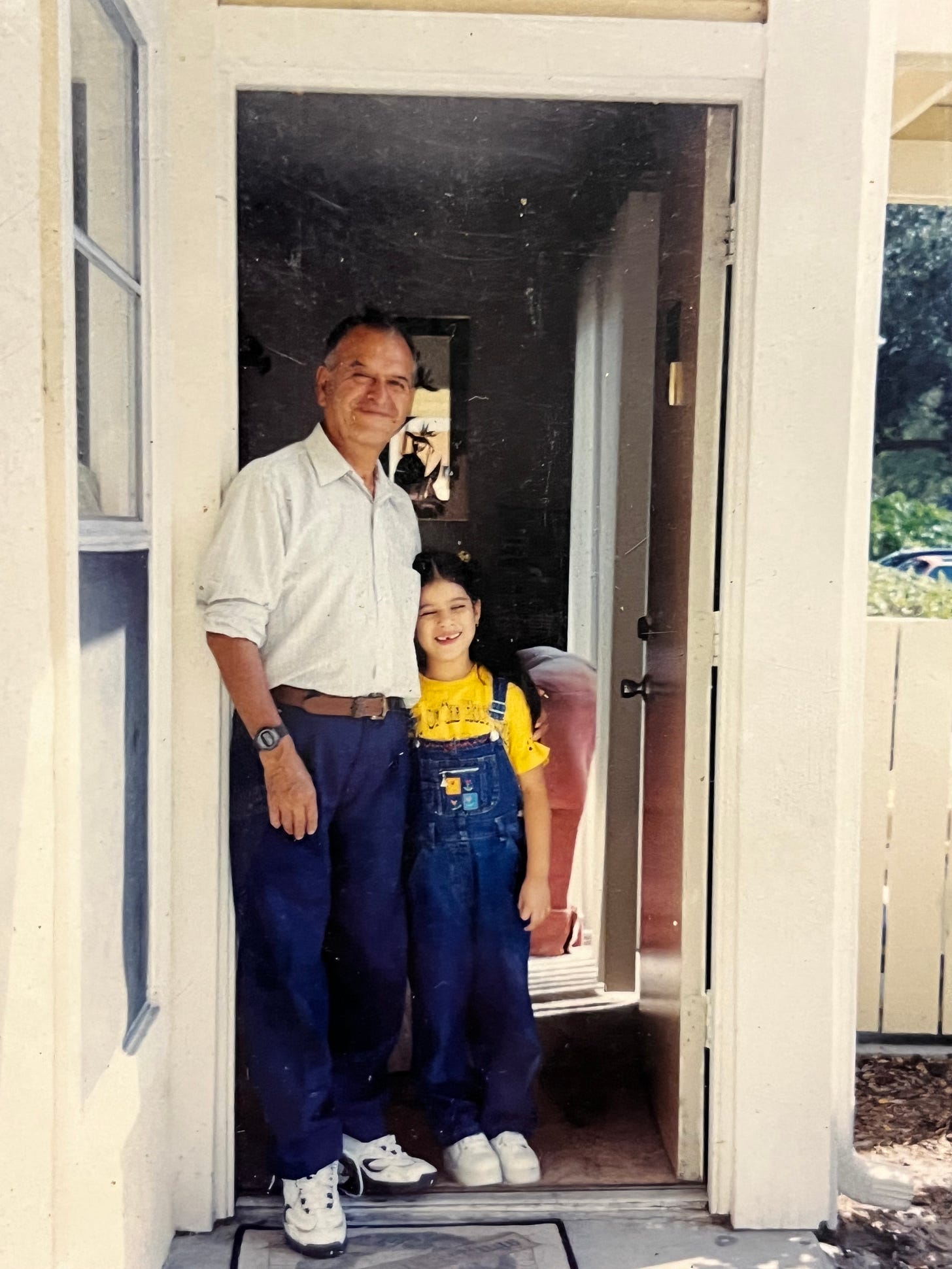

Mi Abuelito y yo. Taken in 1999.

A photo that he had tucked away for me to see for the first time in 25 years.

With love,

-Marisol

a.k.a. Mami soy emo

Thank you for sharing this. As someone who had to euthanize her dog and also lost all her abuelita/os, this really hit home. I'm so sorry, Marisol. But also, I commend you on the threads of humor you wove into this journey through your grief. May they all rest in peace.